Pain – The neuroscience behind and understanding it

Do you suffer from Chronic Pain?

Do you feel misunderstood and frustrated?

Here at Therapia we want you to remember, the concept developed by Mosely and Butler (2017): All pain is normal, all pain is a personal experience and all pain is real.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has classified chronic pain as “pain that persists or recurs for more than three months” (which is longer than the expected healing time of soft tissue), with the exception of pain experienced after some surgeries and some types of traumatic injuries (International Association for the Study of Pain, 2016).

To understand chronic pain, we have to understand why we can have such intense, debilitating pain, when health professionals classify our tissues “normal”.

The following blog helps to explain this.

First we will explain a little bit about inflammation and the nervous system.

Inflammation

Inflammation is the body’s amazing, natural, healing process whereby blood flow to a site of injury is increased and chemicals are released into the area to start healing. Symptoms of inflammation include pain, redness, swelling and heat in the area.

The Nervous System

Nerves originate in our brain and spinal cord. There are two types of nerves.

- Sensory nerves: Detectors which help us to understand what is going on around us and keep sending messages, or inputs, to the brain and spinal cord, to make us aware of our environment and inform us whether it is safe or potentially dangerous. Sensory neurons have input in to the brain and spinal cord.

- Motor nerves: Action causers, which cause us to move, by activating appropriate muscles or glands to release appropriate hormones. They also cause the spark of thoughts, behaviours and beliefs. Motor nerves are responsible for causing our actions based upon the brain and spinal cords calculations and are outputs.

It is hard to believe that pain is actually generated in the brain and is an OUTPUT released when harm is detected.

Basically, when danger is detected, the brain and/or spinal cord send pain to that area, so in turn we protect the threatened tissue by changing our behaviours or positions, for example by limping to reduce weight bearing on a potentially broken foot (Littlewood et al. 2013), or moving our hand away from a flame as shown in the diagram above.

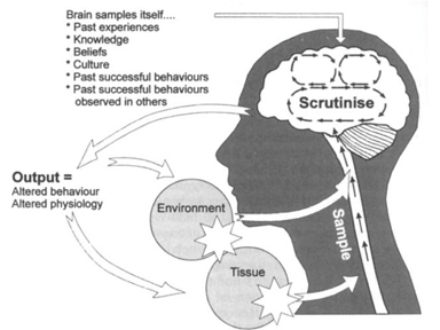

The diagram below, shows a model developed by Griffon (1998), called The Mature Organism Model, this represents this concept very well:

Figure 1: (Gifford 1998)

It highlights that danger detected by sensory nerves from both our environment and our tissue, are sent up the spinal cord to the brain. The brain and spinal cord assess the incoming signals and produce an appropriate output to adapt to remain as safe as possible.

The brain then interprets this information, and determines whether our tissues are in danger or not. If it suspects we are in danger, it produces an output depending on whether we need to protect ourselves or not e.g. movement away from danger, or feel pain in those tissues so that we stop using them.

PAIN

There are three biological mechanisms that can cause an output of pain to be produced:

- Nociception (the detection of danger): the exposure of tissues to harmful stimuli occurs. These stimuli can be: chemical, mechanical (overstretch or compression of tissue leading to damage) or thermal (tissue that is too hot or cold) (Smart 2012b).

- Central sensitization: a dysfunction within the brain and spinal cord is occuring, so that safe, incoming signals are interpreted as harmful (Smart & Keith 2012)

- Peripheral neuropathy: there is damage to the peripheral nerves themselves (all nerves outside of the brain and spinal cord) (Smart 2012a)

It is also important to understand that high stress has also been indicated to increase pain, delays recovery and increases risk of chronic pain development (Lentz et al. 2016).

The next fact is something commonly mistaken.

The amount of pain we feel rarely reflects how much tissue damage there really is (Moseley and Butler 2017).

Think about a paper cut, and how painful this can be. Compare this to cases where people have had their entire leg bitten off by a shark, and have not felt a thing. This is all due to the analysis by the brain and spinal cord of the situation and their believed best response to produce outputs that are most likely to protect the person and give them the best chance of surviving at that given time of detected danger.

Now we will discuss two different types of injury that can occur, both which cause significant pain, yet both which have very different mechanisms of reasons why pain is caused.

BROKEN BONE

Pain reported by a person with a recently broken bone, usually relates well to the extent of the tissue damage and the dominant mechanism responsible for the pain output is nociceptive pain (danger detection through chemical and mechanical changes in the tissue).

MECHANISM – FRACTURE (NOCICEPTIVE PAIN)

Bone tissue breaks due to an inability to withstand the intensity, speed and direction of an applied force. It can be caused by trauma, stress, bone weakness or disease (Westerman & Scammell 2011). Trauma causes sensory nerves to detect a harmful change in shape of tissue, which sends danger signals to the brain and spinal cord. It also causes the release of chemicals that cause inflammation to occur – to kick-start the healing process (Birklein & Schmelz 2008). This sends further danger detector signals to the brain and spinal cord. The brain and spinal cord process the input, identifies threat and outputs pain.

CHRONIC TENDINOPATHY

On the other hand, the degree of pain reported in chronic tendinopathy, does not always relate well to the extent of peripheral tissue damage or pathology, and the dominant biological mechanism responsible for the pain output can be central sensitisation (safe, incoming signals becoming interpreted as harmful by the brain and spinal cord).

MECHANISM – CHRONIC TENDINOPATHY (CENTRAL SENSITISATION PAIN)

Chronic tendinopathy, is an umbrella term for a number of conditions, and refers to a combination of pain and impaired performance of a tendon, which have lasted longer than 3 months (Seitz et al. 2011).

Non-chronic (acute) tendinopathy occurs when there are mechanical changes to the tendon. They are caused by external or internal factors, or a combination of both. Externally, tendon compression occurs, while internally, degeneration occurs (Seitz et al. 2011), both result in inflammation. Therefore both mechanisms produce the detection of harm at the environment and tissues due to chemical and mechanical changes and send this input to the spinal cord and brain, which then outputs pain to the area. This can be seen circled on The Mature Organism Model below:

Amazingly, evidence suggests people experiencing chronic tendinopathy can have minimal or no inflammatory cells in the painful tendons. This suggests there is another reason for their brain to produce an output of pain: an altered processing of input within the brain and spinal cord, so that a threat is still detected despite little tissue damage (Littlewood et al. 2013), this can be caused by a range of things, including previous experiences with pain. For example, if you once had a back injury, and it was painful every time you bent forward, the central nervous system may now associate bending as dangerous and therefore outputs pain to that same area in your back to feel pain before any tissue damage can occur, as a prevention and protection strategy. Again, please see how the listed factors can affect the output produced by the pain, circled on The Mature Organism Model below:

Due to the differences in nature of the pain experienced with both conditions, the management strategies for both of these conditions differs substantially. Please be patient for our next blog describing the different management strategies for each of the different types of pain.

If you found any of this information useful or intriguing and would like to learn more about your pain and you would like to make an appointment with one of our physiotherapists, contact us at Therapia Physiotherapy and Pilates on (08) 8221 6436, or email us at info@therapia.com.au.

References:

Birklein, F & Schmelz, M 2008, ‘Neuropeptides, neurogenic inflammation and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)’, Neuroscience Letters, vol. 437, no. 3, pp. 199-202.

Gifford LS 1998, ‘Pain, the Tissues and the Nervous System: A conceptual model’, Physiotherapy, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 27–36.

International Association for the Study of Pain 2016, IASP Task Force for the Classification of Chronic Pain in ICD-11 Prepares New Criteria on Postsurgical and Posttraumatic Pain, International Association for the Study of Pain, viewed 19th January 2018, < https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=5134&navItemNumber=643>

Lentz, TA, Beneciuk, JM, Bialosky, JE, Zeppieri, G, Dai, Y, Wu, SS, George, SZ 2016, ‘Development of a Yellow Flag Assessment Tool for Orthopaedic Physical Therapists: Results From the Optimal Screening for Prediction of Referral and Outcome (OSPRO) Cohort’, The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 327.

Littlewood, C, Malliaras, P, Bateman, M, Stace, R, May, S & Walters, S 2013, ‘The central nervous system – An additional consideration in ‘rotator cuff tendinopathy’ and a potential basis for understanding response to loaded therapeutic exercise’, Manual Therapy, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 468-472.

Mosely, LG, Butler, DS 2017, Explain Pain Supercharged, Noigroup Publications.

Seitz, AL, Mcclure, PW, Finucane, S, Boardman, ND & Michener, LA 2011, ‘Mechanisms of rotator cuff tendinopathy: Intrinsic, extrinsic, or both?’, Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1-12.

Smart, KM, Blake, C, Staines, A, Thacker, M & Doody, C 2012, ‘Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 1 of 3: Symptoms and signs of central sensitisation in patients with low back (±leg) pain’, Manual Therapy, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 336-344.

Smart, KM 2012a, ‘Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 2 of 3: Symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain’, Manual therapy, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 345-351.

Smart, KM 2012b, ‘Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 3 of 3: Symptoms and signs of nociceptive pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain’, Manual therapy, vol. 17 no. 4, pp. 352-357.

Westerman, RW & Scammell, BE 2011, ‘Principles of bone and joint injuries and their healing’, Surgery (Oxford), vol. 30, no. 2.

Book Appointment